I've simply started plotting through the Dow Jones looking at annual returns year by year. Looking at annual returns is a really arbitrary thing to do since I am picking a price at some "random" date and comparing the ratio of it to some other date in the future. I am sure that picking different windows will have different values but what else am I to do, eh? Not a whole lot until I figure something out, but for now this is it:

I've grabbed annual data back till 1971 and the funny thing about looking at 40 years or annual data is that there is so little data to look at. The first thing that pops out at me is the all negative change years occur after a +10% change year (though not after all 10% years). The second thing is that 5 out of 7 negative years turn positive the year after. So what would you do in this case? One could surmise that it might be a good idea to take out some money after a +10% year and put it elsewhere as a contingent against a negative year (Ie. Bonds or something). The next thing is that you might once a negative year occurs, you have a good probability of catching a positive year after a negative year. Something like that could work but the problem is that you will still need to optimize against having 2 consecutive bad years. There is also a period in the 1990 where there was nearly no negative growth years, but let's say that you've optimized your strategy to factor that in too.

Now suppose that based this 40 years of data you've made a fairly optimized portfolio where you take a small chunk of money during good years and put them into bonds when you make more than 10% when the new year hits and made a rule that if there is a negative year, that you would plunk (say) about 60% of the money you had in bonds into the market during a bad year to catch the probability of a good year the year after and it left you with enough funds to deal with 2 consecutive bad years you could leverage yourself since the probability of having 3 bad years according to this data is zero (the alarm bells should already be going off here).

Suppose that this strategy worked well against this data, you might be fairly tapped out if there are 2 consecutive bad years and the strategy provides for very good gains. Unfortunately, if you look far back enough in history, there is a period right after 1929 where there was 4 consecutive bad years. If a black-swan event like that happened, everything in your portfolio would be gone. Unlike poker, you don't generally have "rebuys" in the stock market (unless you have really rich and possibly foolish relatives), If you're going to want to play this for the long game, developing a methodology to understand what is going on around you, knowing your options, knowing your limits and knowing what exactly you are willing to risk is important. Having good well founded rules to maximize your success are important and you should, in general, play by self set rules that are designed to maximize your chance of success (and though, just like poker, success isn't guaranteed). And just as a note, there are 4 years of consecutive negative growth around 1929 that might have wiped this strategy out (then again, it probably wiped out nearly everyone during that time). In addition, you may want to have a contingency to catastrophic events.

I had this knowledge internalized in me in poker so well that I had forgotten to be aware of my general rules that made me a generally strong player. Most of my poker playing rules were also mathematically generated too, the game of poker (un)fortunately is really easy to analyze. All you need is some general understanding of probability, expected value calculations and knowledge of permutations and you pretty much had it made. The stock market is different and choices and information is so much more vast such that it nearly impossible to understand the entire system... though I still do try (though I am off on a tangent).

Rule number 1, though, it to have a set of rules to play by and more importantly, have a set of mental interlocks to prevent yourself from going "tilt." Getting into the stock market will make one incredibly emotional. A bad stock market period is like PMS for men (that is not to say that only men participate in the market) and you honestly need to get a hold of yourself during those time because you are going to be prone to doing stupid things.

This coming of the second crash (?) has given me a great opportunity to better look in to and handle crashes. The first stock market crash that I have ever had to have deal was the 2008 one, and my, that was a doosie. I wished I was old enough to have participated in the 2000 dot com bust, because I would have been much younger and had a lot less money to lose. Unfortunately, I was too young and had very little real capital to my name during that time (and the cost of trading was way too expensive during that time; $29 for a single trade!). Anyways if/when I do have kids, I am giving them money to blow in the stock market, they might as well learn to lose everything early and fast (and I hope to not make chronic gambling kids while at it too).

Fail Safe (avoiding gambler's ruin)

Unlike other games, the stock market is the kind of game where you play on one "life." The idea that you're supposed to be in the market till about 65 ish (or longer) and not screw up and lose nearly one thing is actually daunting. It's like pretty much saying that for 30-40 years that you are not allowed to fuck up. But that is pretty much it, lose once in the middle of it and you are possibly screwed.

I've come to the realization that optimizing for gain and building a robust portfolio are (to me at least) opposing factors. Optimization is basically trying to allocate resources perfectly to come out with the most perfect result as possible (which is easy in games, hard in real life) because it can equate to doing things with minimal margin for error and going for possibly unrealistic perfect results. When it comes to investing, you are never going to get the most of that up swing, nor are you going to know when the market has hit bottom. The question is not a matter of making the perfect play (because it is impossible), can you make decisions such that are "good enough"? The next important thing is that can you make consistently make "good enough" decisions? Because if you can, then you are on your way to becoming a good investor and I think this is often an overlooked point.

The important thing about investing is being able to quantify the risks of every decision that you make and have a general idea of what you are going to do if things turn bad. How much loss are you willing to take? if losses do occur, are there other assets that can balance against that loss? Is the portfolio setup in a way that you won't be psychologically affected if things go to bad (or good?). Risk quantification in a portfolio is really tough and it is a really fuzzy science but it is very necessary. One of those lessons learned from my crazy crash and burn in 2008.

How am I faring?

I think I was lucky this time because I wasn't overly invested in equities and though the equities that I did hold lost a lot of value, I am sleeping better compared to last time. The other thing I should note was that I was a little impatient in getting back into equities a few months ago when it seemed to me that things were going to start taking off. The equities that I did end up buying were over priced because I thought things were going to be a little better than they currently are right now. I should have been more patient but that is the way how hindsight works.

I've also thankfully kept a good amount of cash out of the markets and will be patient for things to cool down in the market before looking at getting back in. The volatility will be here for a few months until Europe sorts it self out and people get over the S&P downgrade of the US (which ironically, did something good for US treasury sales). There will be plenty of sucker rallies and swings coming up... but then again, that is already pretty normal for the stock market.

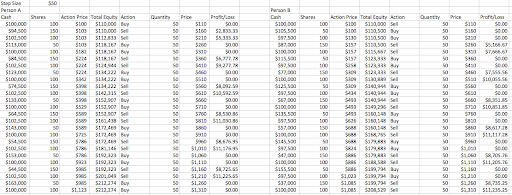

If you can make sense of the following data, then you deserve to be a millionaire.